Promotion

Use LIBRA24 for 15% off site wide + free shipping over $45

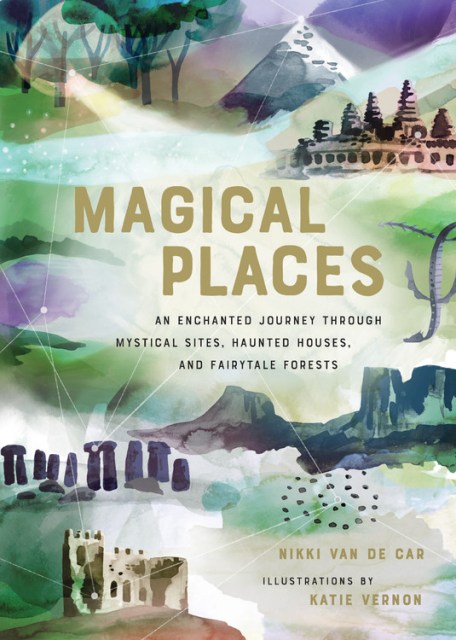

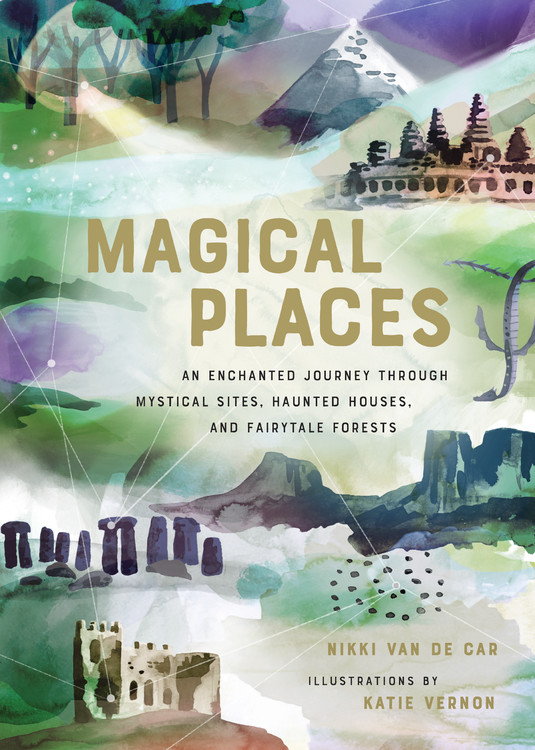

Magical Places

An Enchanted Journey through Mystical Sites, Haunted Houses, and Fairytale Forests

Contributors

Illustrated by Katie Vernon

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.00Price

$23.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $18.00 $23.50 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 4, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An enchanting, illustrated guide to the world’s most magical places, from fairy tale forests to haunted houses, from the author of Practical Magic.

Magical Places is for armchair-voyagers and pilgrimage-makers alike. This beautiful volume will take readers on a charmed journey around the world, dipping into some of the most storied destinations in the farthest flung corners of the globe. With chapters like Places of Healing, Haunted Places, Magic in Nature, Fairy Tale Locales, The Past in the Present, and Ley Lines — the arcing lines that traverse the planet, where magical phenomena frequently occur — wanderlust is sure to be stoked for frequent travelers and the magic curious alike.

With an eye towards the mystical, Magical Places will explore well-known sites like Stonehenge and Uluru, as well as lesser-known destinations like The Knucker Hole in England, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the Fairy Glen on the Isle of Skye, and the pink lakes Retba in Senegal and Hillier in Australia. Many of these sites will be accompanied by sacred rituals, mystical incantations, and more inspired by the energy and history of these magical locations.

Featuring beautiful illustrations with a smattering of lush, full-color photography, this book will entice readers who long for adventure and enchantment in the world, who want to visit or at least learn about places where magic is real — or once was.

- On Sale

- Jun 4, 2019

- Page Count

- 160 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762465972

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use